Seven Ways You Can #DoMore to Prevent Suicide Today

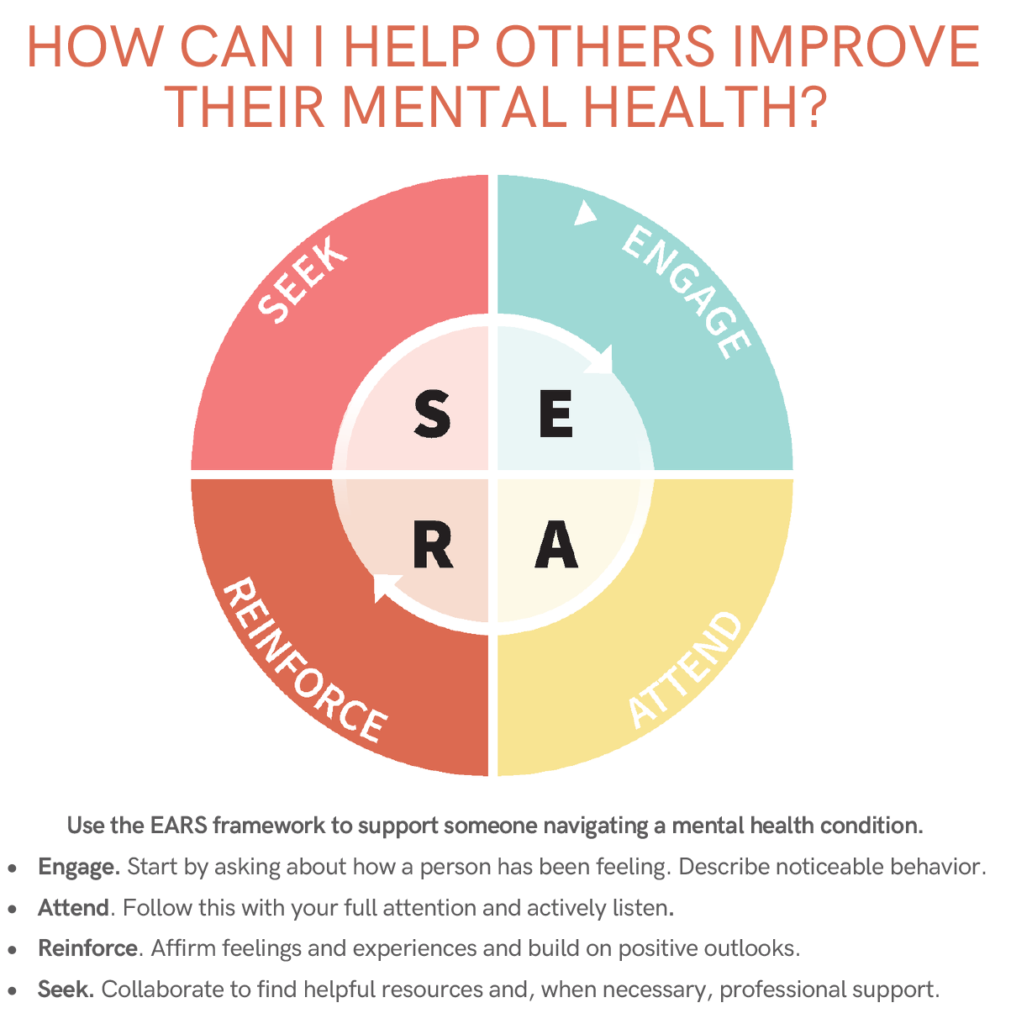

Suicide doesn’t start in a moment of crisis. By addressing the risk factors that contribute to suicide and building up the protective factors that keep people from considering suicide, we can save lives. These seven actions are adapted from the CDC’s seven strategies for suicide prevention. While the CDC’s strategies are largely directed toward mental health professionals and policymakers, there are ways that every one of us can do more to prevent suicide. Read through the list and see how you can take action today to save lives.

1. Help people facing dire financial situations or the loss of housing.

Financial stress, homelessness, or even worries about finances or eviction can increase the risk of suicide. If you know of someone going through a hard time, make sure they don’t feel alone. Work to connect them to resources that can help with both their situation and their mental health. Also, be sure to support policies that ensure people aren’t falling through the cracks.

2. Learn what mental health and suicide prevention resources are available in your area.

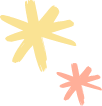

The awareness of the importance of mental health is increasing, and the stigma around talking about and seeking mental health is decreasing. This means you are more likely to hear about someone’s struggles than you might have been even a few years ago. Then the question becomes, how can you help? Lost&Found offers a variety of tools for helpers, starting with the EARS framework (described in Lost&Found’s Let’s Talk about Mental Health Guide) to guide your conversation—engage, attend, reinforce, seek. Prepare yourself for the “seek” part of the conversation—seeking help together—by becoming familiar with the mental health and suicide prevention resources available in your area. Lost&Found’s Resources page provides a good overview. The first and easiest resource to become familiar with is this number: 988. This goes to the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, and it can be reached by calling or texting.

Here is an overview of the EARS framework. Find more information about the EARS framework in the Let’s Talk About Mental Health Guide.

3. Reduce access to lethal means in your home, workplace, and community.

Two key pieces of data support this action: First, research shows that attempting suicide is often an impulse based on an intense emotion—the time between deciding to act and attempting suicide can be as little as 5 or 10 minutes. Second, if a person chooses a highly lethal method of suicide, but that method is not available, they tend not to substitute a different method. This means that if we can stretch the time between the decision and the attempt, and if we can make lethal means harder to access, we can save lives. Make sure medications and firearms are safely stored—in other words, behind a lock—in your home. Also look around your workplace and community—if there are places such as bridges where a suicide could take place easily, consider installing signs to encourage people to seek help.

4. Get involved in your community, and work to include those who might be isolated.

Studies suggest there is a correlation between social capital—meaning the sense of trust in a community and the connections between its members—and mental health. This means that all sorts of things that might not seem directly connected to mental health, such as knowing and interacting with your neighbors, block parties, and community improvement projects, are actually long-game suicide prevention strategies. In school settings, this can include participating in clubs or sports, as well as peer support programs. Consider how you could help build social capital in your community. If you are already involved in your community, invite someone else to participate with you to draw the circle of community support a little bigger.

5. Commit to learning—and teaching—how to deal with conflict.

Having the skills to deal with the stresses and adversities of life can help protect people from turning to suicide as an option. Programs that teach these skills, such as social-emotional learning programs for children and teens, or parenting skills and family relationship programs, can give people tools for dealing with problems—and, just as important, they can plant the idea that life’s problems can be solved, or at least managed and improved. One life skill that can help decrease stress and build relationships is learning how to deal productively with conflict. As polarization in society increases and gives people the idea that animosity in the face of conflict is a virtue, knowing how to address conflicts productively is a vital skill. This article on the basics of dealing with conflict in relationships is a good place to start.

6. Work to be accepting of people in marginalized demographic groups that are at higher risk of suicide.

Some groups have higher rates of suicidal behaviors than average. They include people with lower socio-economic status, people with a mental health problem, people who have previously attempted suicide, veterans and active military, people who are the victims of violence, LGBTQIA2S+ people, and members of some racial and ethnic groups. One group that is at higher risk is LGBTQIA2S+ youth. A Trevor Project survey found that 45 percent of LGBTQ youth had seriously considered suicide in the past year, including more than half of transgender and nonbinary youth; 14 percent of LGBTQ youth had attempted suicide in the past year. The survey also pointed to an obvious way to help: suicide attempts were significantly lower among LGBTQ youth that were in accepting communities or who had accepting family and friends. Accepting LGBTQIA2S+ youth for who they are can save lives.

7. Learn how to talk about suicide in ways that don’t add to the trauma of those who have suffered a suicide loss.

The risk of suicide is higher for people who have lost a friend, family member, or other close contact to suicide. While talking about suicide is important—not talking about suicide can feed into a sense of shame for survivors of suicide loss—knowing how to talk about suicide is just as important so we don’t inadvertently add to a survivor’s pain. For example, one phrase to remove from your vocabulary is “committed suicide.” “Committed” is left over from the outdated belief that suicide is a criminal act. It’s better to say “died by suicide.” There are more suggestions for how to talk about mental health and suicide on page 26 in Lost&Found’s Let’s Talk About Mental Health Guide—download it free here.

You can review the CCD’s seven suicide prevention strategies here. Click on the image to see the full report.

This article is part of the 30 Days, 30 Stories: Let’s #DoMore to Prevent Suicide project. See a new story of resilience for every day of National Suicide Prevention Month here.